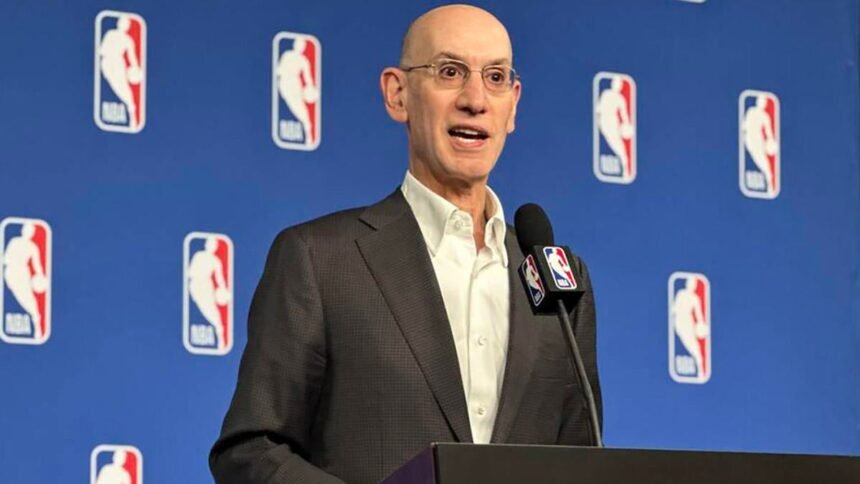

The NBA has had 30 teams for the past 20 years. The Charlotte Bobcats joined the league for the 2004-05 season, and they played their first game on Nov. 4, 2004 — exactly 20 years ago. Despite years of rumors, no new teams have been founded since. But rumors of expansion have grown louder and louder in recent years. First, the COVID-19 pandemic made the idea of a quick cash infusion very attractive to the league. Then, the NBA put expansion on the back burner while it negotiated a new CBA. After the CBA, the media deal came next. But commissioner Adam Silver was straightforward as all of this played out. The league had other priorities in those moments, but expansion was something that would be considered in the future.

Well, the future may not have arrived, but it’s rapidly approaching. The league and its players agreed to that new CBA in 2023. The new media deal followed a year later. Expansion hasn’t been announced formally yet, but it appears inevitable. Last month, the Clippers and Trail Blazers played a preseason game in Seattle, a former NBA market that is rumored to be getting a new team in future expansion.

The widespread assumption is that new teams are coming. Then what? How are these teams formed? How will their presence impact the league? Where will they play? Below is a guide to how exactly expansion works. Keep in mind that the NBA has not actually expanded in two decades. It is possible that the league tweaks certain rules and precedents this time around. But broadly speaking, here is how the expansion process works.

How do expansion teams work?

Think of the NBA as a single business divided into 30 pieces: the 30 teams. When a new owner wants to buy into the NBA, most of the time, that owner is buying one of the 30 pieces from another pre-existing owner. Expansion works slightly differently. Instead of buying one of the 30 pieces that already exist, that new owner is instead asking each of the 30 owners to sell him a small percentage of their overall equity in the league, effectively creating a 31st piece (a new team).

Put more simply: a new owner is buying a team that does not exist and paying each of the existing owners an expansion fee for the right to create it. That fee is divided evenly among the existing owners. They get an immediate cash infusion equal to 1/30th of the fee, but moving forward, their overall equity in the league is slightly diluted because there is now a new partner eligible to share in league-wide revenue.

There is no firm rule on how much a new owner would need to pay the league for the right to expand, but generally speaking, expansion fees are slightly more expensive than buying an existing team in a similar market would be. When the Bobcats joined the league in 2004, for instance, they paid a $300 million expansion fee. Four years earlier, the Dallas Mavericks were sold for $285 million despite playing in a better market.

Similarly, the Boston Celtics, one of the league’s most valuable franchises, sold for $360 million two years before the Bobcats joined the league. That’s only a 20% premium over what the Bobcats paid. Forbes, by comparison, currently estimates that the Celtics are worth 1.56 times as much as the Hornets. However, expansion teams tend to cost a premium because existing owners want to be sure they are paid enough to warrant splitting future league revenue with an extra partner.

So how much would new owners need to pay for the right to expand? Expect the price to break records. When $2.5 billion per team was the reported number in 2021, Silver called that reported number “very low.” Every team sold in the past two years has valued the franchise at $3 billion or more. The current high-water mark is $4 billion, which Mat Ishbia paid for the Phoenix Suns. Remember, the markets in play this time around are more valuable than Charlotte. It’s hard to imagine a starting point any lower than $4.5 billion, with the possibility of that number going up in a bidding war. If two teams joined the league at $4.5 billion each, the 30 current owners would receive $300 million each. Keep an eye on the sale of the Celtics, which is coming in the near future. That number could set a benchmark that the expansion teams need to reach or at least approach.

Notably, the owners would not have to share that money with the players. Only owners cash in on expansion fees. These are not considered basketball-related income, so players are not entitled to a cent according to the collective bargaining agreement. Of course, that doesn’t mean players don’t benefit. They just do so through other means.

Ok, so what’s in it for the players?

In short: jobs. Two more teams mean 30 more full-time roster spots, six more two-way spots, four more draft picks every year, and most importantly, two new possible bidders for their services in free agency. Those benefits mostly affect fringe players, but remember, superstars don’t comprise the majority of the player’s union. Rank-and-file members exist in a fairly precarious state. All it takes is one injury or one down year to seriously impact their career prospects. Having those extra jobs available really matters.

The stars don’t benefit quite as much. They’ll get paid either way. But hey, it never hurts to have another source of leverage. Suddenly they have two more possible destinations when they ask for trades. They might even prefer the lifestyles available in the two new cities, and these teams could quickly become glamour franchises.

And, of course, these new jobs aren’t just available to players. Two more teams mean two more head coaches, two more general managers, two more front offices filled with different kinds of basketball thinkers. This matters more than it might appear. If more teams are sharing the same talent pool, it incentivizes innovation. More teams could mean more diversity in playing style. Players that are struggling to get paid now might do better in a less stylistically homogenous league. The more teams that exist, the more possible fits there are for everybody in the league. In that sense, players benefit quite a bit in the long run even if they don’t see the immediate financial benefit of sharing in expansion fees.

We know the benefits, but what are the downsides?

There’s only one word you need to know here: “dilution.” It affects every element of the sport, but some more than others. For the owners, it comes in the form of revenue. Where they once split the league’s enormous national television pie 30 ways, they would now have to split it 32 ways.

That is true of all shared league revenue, and it trickles down to the players in the form of the salary cap. The cap is 44.74% of projected basketball-related income for the upcoming season, divided by the number of teams in the league. Dividing by 32 instead of 30 means that the cap would be slightly lower on a relative basis.

Speaking of the players, it’s not as though adding new teams magically expands the pool of available players. The more teams there are, the thinner the league’s existing pool of talent is stretched. This was felt most acutely during the expansion boom of the late 80s and 90s. The bad teams were worse because they were so new, but the good teams were also worse because players that might otherwise have been effective supporting pieces for them were suddenly headlining expansion teams.

Fortunately, on almost every front, these problems are less serious today than they have been in the past. Consider the player pool. Not only has the NBA seen a massive influx of foreign-born talent that it didn’t have decades earlier, but it also has a fully functioning minor league system in the form of the G-League that is developing younger players. Both sources of talent are growing, not shrinking. The league can absolutely support two new teams. If anything, the presence of two new teams might help the league discover worthwhile players who might not otherwise have gotten a shot.

Thanks to cap smoothing, the cap isn’t really going to be affected either. The new collective bargaining agreement ensures that the cap can rise no more than 10% annually every year. This matters because the new TV deal, left to its own devices, would spike the cap far more than that. In other words, there is surplus revenue here. That money would have gone to the players eventually either way, as neither the players nor the owners can ever earn more than 51% of BRI in a given season, but this giant infusion of television money is so big that it should be able to support 10% annual growth comfortably even with two new teams splitting up the pie.

Owners are affected in one other way, but even that doesn’t mean quite as much as it once did. If two new markets suddenly join the league, those markets no longer exist as threats to existing cities that are hesitant to help pay for new stadiums. Most sports leagues like to have a few viable cities in reserve so they can threaten to move teams there if needed. Of course, the NBA hasn’t moved a team since the Sonics left Seattle in 2008, and no team has really come close since the Kings almost moved to Seattle in 2013. Generally speaking, NBA teams and their cities have been able to effectively negotiate stadium deals over the past decade without using relocation as a serious threat. The league is healthy enough that it doesn’t need to hold certain markets over anybody’s head.

How do expansion teams fill out their rosters?

Expansion teams start as blank slates. The majority of their rosters come through a process called the expansion draft. In this exercise, teams are allowed to protect a certain number of players (in 2004, it was eight, but if a team had fewer than that under contract they had to make at least one player available), but anyone they don’t protect can be selected by the expansion teams to join their rosters. Teams can only lose one player per expansion draft, so the field whittles down quickly. Most of the players available in the expansion draft are old, injured or have bad contracts, but the occasional gem slips through the cracks. The Bobcats got future All-Star Gerald Wallace in 2004, for instance. B.J. Armstrong, Rick Mahorn and Walt Bellamy are a few other big names that have been taken in expansion drafts.

Expansion teams also draft players in the traditional NBA Draft, but they are typically not allowed to participate in the lottery drawing. The Bobcats were locked in at No. 4 overall in 2004, but traded up to No. 2. In 1995, the Grizzlies (No. 6) and Raptors (No. 7) were locked in at slightly lower slots. Expansion teams do not begin drafting under the year before they are set to play.

Free agency is also available to expansion teams, but doing so isn’t exactly easy. Expansion teams are only allowed to spend up to two-thirds of the salary cap in their first season and 80% of it in their second. Finally, in their third season, expansion teams can access the full cap.

So where are these two teams going to play?

Let’s address the elephant in the room here: the widespread expectation is that Las Vegas and Seattle will be our two new expansion markets. Seattle already had a team for more than four decades. That team now plays in Oklahoma City, a much smaller market. Vegas has never hosted an NBA team, but it has been one of the league’s unofficial West Coast headquarters (along with Los Angeles). It hosts Summer League every year. It has hosted an All-Star Weekend. It just hosted the inaugural NBA Cup final last December and will host the event’s title game again this year. It has been an NBA city for some time. The league just needs to make it official with its own team. LeBron James has openly campaigned to own it.

Seattle and Las Vegas are the two right markets for new NBA teams. Both of them already have NBA-ready arenas. Seattle has Climate Pledge Arena, where the NHL’s Kraken play and it has now hosted preseason games in both 2023 and 2024. Vegas has T-Mobile Arena, which hosted the In-Season Tournament final. Seattle is the nation’s 13th-biggest market and the second-biggest that does not currently host an NBA team (behind Tampa Bay-St. Petersburg). Vegas is smaller, but sustains itself through tourism. NBA teams need concentrated wealth to thrive, as luxury suites are a major driver of revenue. The Seattle tech scene and the Nevada gambling industry both qualify. Barring something unforeseen, these are the likeliest new cities to join the NBA.

Are there any other contenders? Anaheim has an NBA-ready arena in the Honda Center, but with two teams in Los Angeles, it’s unlikely that the league would want to put a third in southern California. Kansas City is an interesting market with a viable arena (the T-Mobile Center). It’s not very big, but there isn’t another NBA market within 350 miles. But the Chiefs and Royals are both having issues funding stadium renovations, so Missouri has other issues to deal with before it’s going to seriously consider ever funding renovations or tax breaks for an NBA team. Louisville almost snagged the Grizzlies two decades ago, and it, too, has an NBA-caliber arena in the KFC Yum! Center, but it would immediately become the NBA’s third-smallest market, ahead of only Memphis and New Orleans. None of these cities represent the complete package that Seattle or Las Vegas could be.

There’s one major wildcard here, and that’s Mexico City. While Vancouver did not work as a foreign NBA market, Toronto absolutely has, and expanding the league’s international reach has always been a major priority. Silver has stated publicly that the NBA would consider expanding to Mexico City, and it brings things to the league that no other market would. Recent estimates suggest that Mexico City has a population of roughly nine million people. That would be the biggest city in all of North American professional sports, and no other league has ever expanded there. The nation of Mexico as a whole has 130 million people, all of whom would be possible fans of the team. Mexico City Arena is a state-of-the-art facility that seats 22,300 fans. The league has played 32 games in Mexico City since 1992. It will play a 33rd on Monday night as the Wizards and Heat play at 9:30 p.m. ET.

But there are real question marks to consider in Mexico City as well. A big one would be player pushback. In its early years, the Canadian teams had real trouble convincing top players to play for them. B.J. Armstrong, the top pick in Toronto’s expansion draft, forced a trade to Golden State. Steve Francis, the No. 2 overall pick in 1999, forced a trade out of Vancouver. Players can’t directly prevent a city from being chosen, but they do have a powerful union that can cause problems for the league in other ways. If the players are adamantly opposed to playing in Mexico, the league would at least listen. Even if players buy in, elevation is another major issue. Mexico City sits at 7,349 feet above sea level. That’s more than 2,000 feet higher than Denver, which currently leads the NBA in altitude. The thinner air in high-altitude cities has a real effect on gameplay, and that might not be something the NBA wants to deal with.

Mexico City is the high-risk, high-reward option. Vegas and Seattle are sure things. Other cities might eventually factor into the bidding, but they’ll all be facing uphill battles.

What other logistical issues would the NBA need to solve?

There are two big issues to sort out here, and one of them could actually have a very significant effect on future championship races, depending on when these new expansion teams join the league. Let’s assume, for now, that our two new markets are Seattle and Las Vegas. Well, both of those cities would have to be in the Western Conference. That means that one current Western Conference team would have to move to the East. So who would it be? Three teams have real arguments, and all three of them are poised to contend for the foreseeable future:

- Memphis, geographically speaking, is the Western Conference city that is furthest east.

- Minnesota is the Western Conference team that is the closest geographically to the most Eastern Conference teams, as Milwaukee, Chicago, Indianapolis, Detroit, Cleveland and Toronto are all relatively short flights away.

- New Orleans isn’t as close to quite as many Eastern Conference teams as Minnesota, but it forms a comfortable southeastern pod with Atlanta, Orlando and Miami. This is valuable if the NBA decides to follow the NFL’s divisional format of four divisions with four teams apiece. The remaining 12 Eastern Conference teams are all relatively close to one another and could easily pair off into four-team divisions. Milwaukee, Chicago, Indiana and Detroit would form one. Boston, New York, Brooklyn and Philadelphia would form another. Finally, Toronto, Cleveland, Washington and Charlotte would join as the union of slight misfits. There are workable versions of this plan in which Charlotte goes off with the southern teams and Minnesota fits with the midwest group, but they aren’t quite as easy to piece together.

Given how unbalanced the conferences have been for the past 25 years, it stands to reason that all three teams would prefer to move East. All three have likely lobbied to do so. It is unclear at this stage which of them would actually get to, but the “winner” here may get an easier path to the NBA Finals moving forward. That could change the entire career trajectories of Anthony Edwards, Ja Morant and Zion Williamson.

The other issue the league needs to solve is the schedule. The NBA’s 82-game schedule is a bit messy right now. Before this season, teams played their divisional opponents four times, their non-conference opponents twice, and then played six of their remaining 10 conference opponents four times and the other four three times to get to 82. The In-Season Tournament has already thrown a bit of a wrench into this approach as it demands that teams play certain opponents more or less depending on the tournament’s results. Without knowing how the tournament will change with time, it’s impossible to say what the league’s scheduling demands will be moving forward, whether there are 30 teams or 32.

Here’s a thought: with 32 teams, the schedule could actually come together fairly cleanly. Imagine teams are split into four-team divisions. They could play their divisional opponents four times each (12 total games), their other conference opponents three times each (36 total games) and their non-conference opponents twice each (32 total games). That takes the NBA schedule up to 80 games with a fixed formula. The remainder of the schedule could be filled in with the In-Season Tournament in whatever form that takes. Perhaps having 80 fixed games would allow for the In-Season Tournament to more easily become a single- or double-elimination tournament instead of an event in which most teams play similar amounts of games (even though some are reduced to simple regular-season affairs).

Any closing thoughts?

It’s time. The NBA has been ready for expansion for years now, and as the NFL has proven, 32 is a more elegant number for a professional sports league than 30. It’s better to have an even number of teams in each conference. Four divisions allow for better in-division rivalries. The talent pool is more than deep enough to sustain two new teams. Interest in the sport is high enough for two new cities to support their own teams. The league has had other priorities over the past decade or so, but the sport is in a very healthy place right now. If ever there was a time to expand, it would be now.

Looking for more NBA coverage? John Gonzalez, Bill Reiter, Ashley Nicole Moss and special guests dive deep into the league’s biggest storylines daily on the Beyond the Arc podcast.